1 | Key Points

- Borrowing authority in Ontario is granted through Orders in Council (OICs) made under the Ontario Loan Act and the Financial Administration Act. The Ontario Loan Act provides the authority for new borrowing while the Financial Administration Act authorizes borrowing for the refinancing of debt maturities.

- In the March 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update (March Update), the government projected a total funding requirement of $49.7 billion, based on an estimated budget deficit of $20.5 billion in 2020-21.

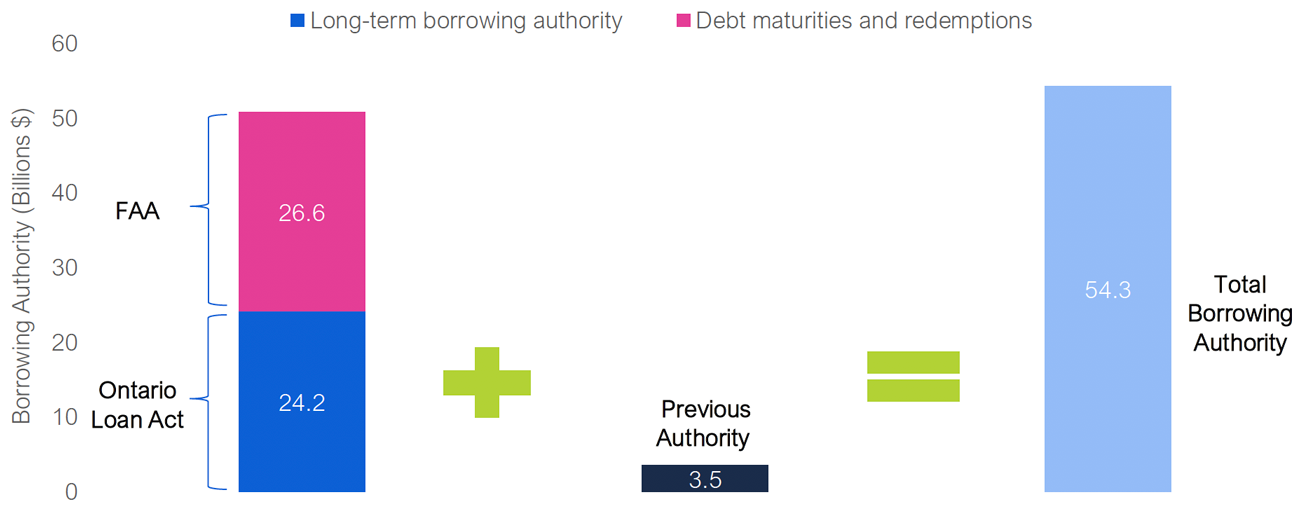

- Based on the fiscal outlook in the March Update, the Province has borrowing authority of $54.3 billion, with $24.2 billion authorized by the Ontario Loan Act, 2020, $26.6 billion authorized by the Financial Administration Act, and $3.5 billion from previous Loan Acts.

- However, in the 2020-21 First Quarter Finances the government updated its forecast for the budget deficit to $38.5 billion, raising the funding requirement to $66.7 billion. Given the higher funding requirement, the FAO expects the government will be required to seek significant additional borrowing authority for 2020.

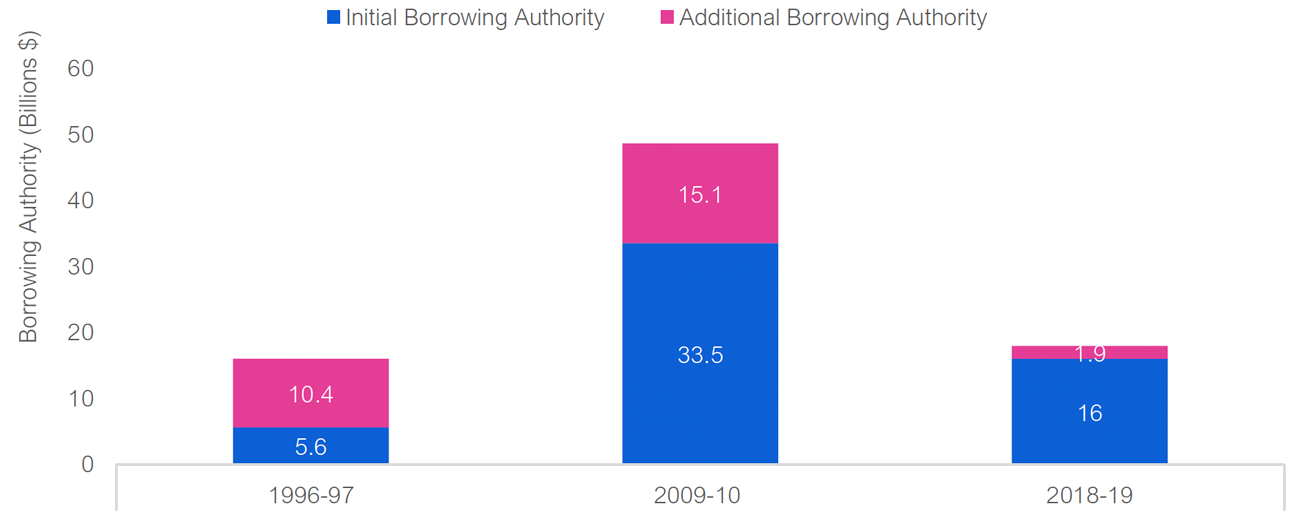

- In the past, any increase in the Province’s funding requirement has been addressed by requesting additional borrowing authority through a second Ontario Loan Act. This occurred most recently in 2009-10 and 2018-19.

2 | Context and Objective

Introduction

Provincial governments require the legal authority from the legislature to borrow (“borrowing authority”) both to issue new debt or refinance existing debt securities. In Ontario, the legislature grants this authority through the Ontario Loan Act and the Financial Administration Act which allow the government to borrow through the issuance of debt securities. Under these Acts, the government creates Orders in Council (OICs) for specific amounts to be borrowed.[1] The Minister of Finance recommends new OICs to Cabinet and the Lieutenant Governor in Council.

The request for borrowing authority in a fiscal year incorporates the Province’s estimated total funding requirement[2] for the year and other strategic considerations. Importantly, although borrowing authority is approved each fiscal year and is related to the financing needs of the fiscal year, it is designed to be flexible so that the use of borrowing authority can span several years. Borrowing authority granted in a specific fiscal year is the sum of OICs approved by the legislature for new long-term borrowing as well as the refinancing of debt that has matured.

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to result in a dramatic increase in Ontario’s budget deficit in 2020-21, pushing the Province’s funding requirement higher and resulting in significant additional provincial debt. In the March 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update, the government projected a deficit of $20.5 billion in 2020-21. Given the government’s March forecast for the deficit, borrowing authority of $50.8 billion was authorized to cover an expected total funding requirement of $49.7 billion.

However, in the 2020-21 First Quarter Finances, the government updated the forecast for the budget deficit to $38.5 billion, raising the funding requirement to $66.7 billion.[3] The much larger expected deficit for 2020-21, compared to the March Update, will result in the need for additional borrowing authority.

Objective

The objective of this report is to provide an overview of the Government of Ontario’s (the Province’s) borrowing authority, including the process of how borrowing occurs and the reporting responsibilities of the government with respect to its borrowing.

This report is structured as follows:

- Chapter 3 presents an overview of borrowing authority legislation and a discussion of trends in Ontario’s borrowing authority over time.

- Chapter 4 provides an explanation of Ontario’s borrowing authority for 2020-21 and describes how additional borrowing authority may be required due to a larger than projected budget deficit as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Chapter 5 discusses trends in the Province’s long-term debt issuance, and the investor profile of Ontario’s debt.

- The Appendix provides additional information on:

- the background, organizational structure and responsibilities of the Ontario Financing Authority (OFA), and

- borrowing authority in other Canadian jurisdictions.

3 | An Overview of Ontario’s Borrowing Authority

Borrowing Authority Legislation

To fulfill Ontario’s short and long-term borrowing requirements, the Province must have the legal authority to borrow. This legal authority is derived from the Ontario Loan Act and the Financial Administration Act. The government creates Orders in Council (OIC) to authorize borrowing amounts under each of these Acts. The Minister of Finance recommends new OICs under these Acts to Cabinet and the Lieutenant Governor in Council as needed. The Minister’s recommendations are based on the borrowing requirements identified by the Ontario Financing Authority.[4] The Ontario Financing Authority oversees Ontario’s borrowing and acts at the discretion of the Province on matters related to borrowing authority.

The Ontario Loan Act allows the government to issue new short or long-term debt up to a specified maximum. To carry out borrowing authorized under an Ontario Loan Act, OICs must be approved outlining the details of the borrowing (e.g. short-term or long-term maturities). Short-term borrowing authority is revolving and can be carried forward until it is fully depleted. Long-term borrowing authority generally extends over a three-year period. The total amount of borrowing authorized by the OICs cannot exceed the maximum specified by the Ontario Loan Act.

The amount of borrowing authority created under the Ontario Loan Act is determined by the government’s fiscal plan presented in budget documents at the time the borrowing authority is requested. Since the government’s fiscal position changes annually, borrowing authority also varies and reflects the government’s forecast for funding requirements for the current fiscal year. Given that borrowing authority spans multiple years, the Province is permitted to pre-borrow for the following fiscal year to take advantage of market opportunities. If the Province has not used the borrowing authority by December 31st of the third year,[5] the OIC expires.

The Financial Administration Act (FAA) provides borrowing authority specifically to refinance debt that is due to be repaid, having reached the end of its term (debt maturities), and debt that has been issued but cancelled (debt redemptions). Borrowing authority under the FAA can also extend backwards, to debt that matured at any time during the previous year. An OIC under the FAA is effective for two years after the date the OIC is approved. Any borrowing authority that remains at the end of the two-year period expires.

In other provinces, borrowing authority is governed by similar legislation as in Ontario; however, there are a number of differences in the borrowing authority framework at the provincial level.[6]

A Profile of Ontario’s Borrowing Authority since 2009

This section provides an overview of total borrowing authorized in a given fiscal year over the past decade.

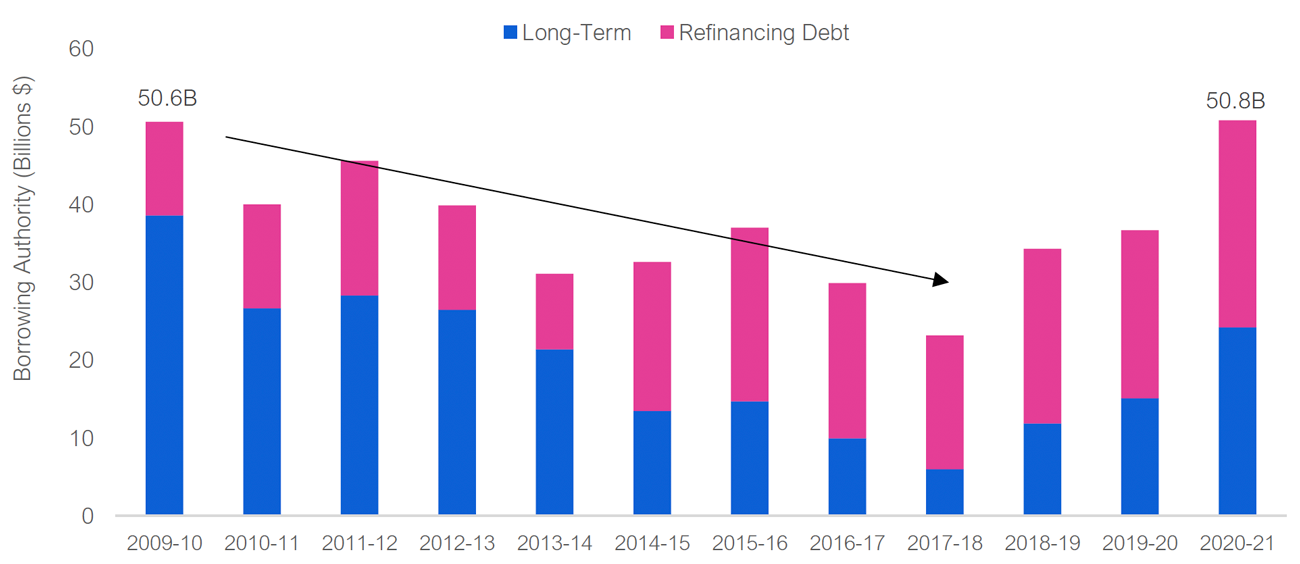

In 2009-10, Ontario’s long-term borrowing authority reached a record high $50.6 billion, reflecting the sharp increase in the budget deficit that year due to the global financial crisis. As the economy recovered and the budget deficit declined, annual long-term borrowing authority amounts decreased to $23.2 billion by 2017-18. Over the past three years, higher deficits combined with elevated refinancing needs have resulted in an increase in annual borrowing authority amounts. For 2020-21, the Province is currently authorized to borrow $50.8 billion, slightly higher than the authorized borrowing in 2009-10.

In 2009-10, the Province’s borrowing authority was mainly used to issue new long-term debt, with less than a quarter of overall borrowing being used to refinance maturing debt. Over the past ten years, as Ontario’s overall indebtedness has increased, a larger proportion of annual borrowing has been needed to refinance or roll-over existing debt that has reached maturity. Based on the government’s current plans, borrowing authority for 2020-21 would be allocated approximately equally between the issuance of new debt and refinancing of maturing debt.

The Province also receives authority under Ontario Loan Acts to increase its short-term borrowing program to ensure the government has access to adequate liquidity to meet its financial obligations. In 2020-21, the Province’s short-term borrowing program has borrowing authority of $55 billion.

Chart 3.1 Total Borrowing Authority Approved by the Legislature Each Fiscal Year

Note: Total borrowing authority is the sum of approved borrowing authority in the fiscal year for long-term borrowing under the Ontario Loan Act and debt refinancing under the FAA. Total borrowing authority reflects multiple OICs and does not have to be used in the fiscal year that it is approved.

Source: OFA, and FAO.

Accessible version

This is a bar chart showing the total borrowing authority approved by the Ontario Legislature in each fiscal year beginning in 2009-10 to 2020-21. Each bar shows the total borrowing authority as the sum of long-term borrowing and debt refinancing. The chart highlights a $50.6 billion borrowing authority in 2009-10 and a downward trend of borrowing authority to 2017-18. The chart also highlights a $50.8 billion borrowing authority for 2020-21.

4 | Understanding Ontario’s Borrowing Authority in 2020-21

2020-21 Borrowing Authority

The Ontario government currently has the authority to conduct long-term borrowing of $54.3 billion in 2020-21 through OICs approved so far under the Ontario Loan Act and the Financial Administration Act.

The Ontario Loan Act, 2020 has authorized $24.2 billion of long-term borrowing to be used by December 31, 2023. The Province also has $26.6 billion in borrowing authority under the Financial Administration Act, to refinance debt maturing in 2020-21.

Combined, the Ontario Loan Act and the Financial Administration Act provide the government with $50.8 billion of approved borrowing authority for 2020-21. Including $3.5 billion in pre-existing borrowing authority from previous Ontario Loan Acts, the government currently has access to $54.3 billion in total borrowing authority for 2020-21.

Chart 4.1 $54.3 billion of Borrowing Authority in 2020-21

Note: Total borrowing authority does not include a $7 billion increase in short-term borrowing to expand the Treasury Bill Program approved by the Ontario Loan Act, 2020 and $7.6 billion in pre-borrowing from 2019-20.

Source: OFA, and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart breaks down the total borrowing authority for this fiscal year. The chart shows that approved borrowing authority is $50.8 billion, the sum of $24.2 billion of long-term borrowing authorized by the Ontario Loan Act and $26.6 billion to refinance debt maturities and redemptions under the Financial Administration Act (FAA). The chart also shows that $3.5 billion of previous authority is combined with these amounts to equal $54.3 billion of total borrowing authority in 2020-21.

The current request for borrowing authority reflects the government’s forecast at the time of the March Update for long-term funding requirements in 2020-21, combined with short-term borrowing needs and other financial considerations. In the 2020 First Quarter Finances, the government updated its estimate of the long-term funding requirement from $49.7 billion to $66.7 billion. As a result, the total borrowing authority of $54.3 billion would be inadequate to meet the government’s expected funding requirement.

Additional Borrowing Authority Expected to be Required

The current borrowing authority in 2020-21 is based on the government’s March Update projection for a budget deficit of $20.5 billion, which was developed before the extent and depth of the economic impact from the COVID-19 pandemic had become fully apparent.

In the 2020-21 First Quarter Finances, the government updated the forecast for the budget deficit to $38.5 billion, raising the funding requirement to $66.7 billion. As a result, the FAO expects that the government will need to request additional borrowing authority from the legislature to meet its funding requirements in 2020-21.

Typically, a single Ontario Loan Act is passed each year, which is intended to provide sufficient borrowing authority for new debt in that year. However, in the event of unforeseen circumstances that increase borrowing requirements, the government can request additional borrowing authority through a second Ontario Loan Act. There have been three years, when a second Ontario Loan Act was required to authorize additional borrowing authority, including 1996-97, 2009-10 and 2018-19.[7]

The FAO’s expectation of the need for additional borrowing authority for 2020-21 is similar to the circumstances in 2009-10, when an economic downturn and higher than expected deficit resulted in the requirement for $15 billion in additional borrowing authority approval.

Chart 4.2 Ontario’s Past Requests for Additional Borrowing Authority

Note: Initial borrowing authority amounts refer to initial OICs authorized. Additional borrowing authority refers to the subsequent OIC authorizing further borrowing authority to cover higher than expected funding needs.

Source: OFA, and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows three fiscal years when a second Ontario Loan Act was required to authorize additional borrowing authority: 1996-97, 2009-10, and 2018-19. The chart highlights that the additional borrowing authorities in each year were $10.4 billion, $15.1 billion, and $1.9 billion, respectively.

5 | Overview of Ontario’s Debt Issuance

Ontario’s Long-Term Debt

The Province has established several programs to meet its borrowing requirements through the issuance of bonds in domestic and foreign capital markets. Debt is issued throughout the year under several borrowing programs,[8] and varies in the amount issued, term structure, and currency. The most common term structure for the issuance of bonds is five, 10 and 30-year terms. Each bond issue has guidelines for minimum amounts to be raised depending on term structure. For example, domestic five-year bonds are required to raise a minimum of $1 billion, 10-year bonds to raise at least $750 million, and 30-year bonds are to raise a minimum of $600 million.[9]

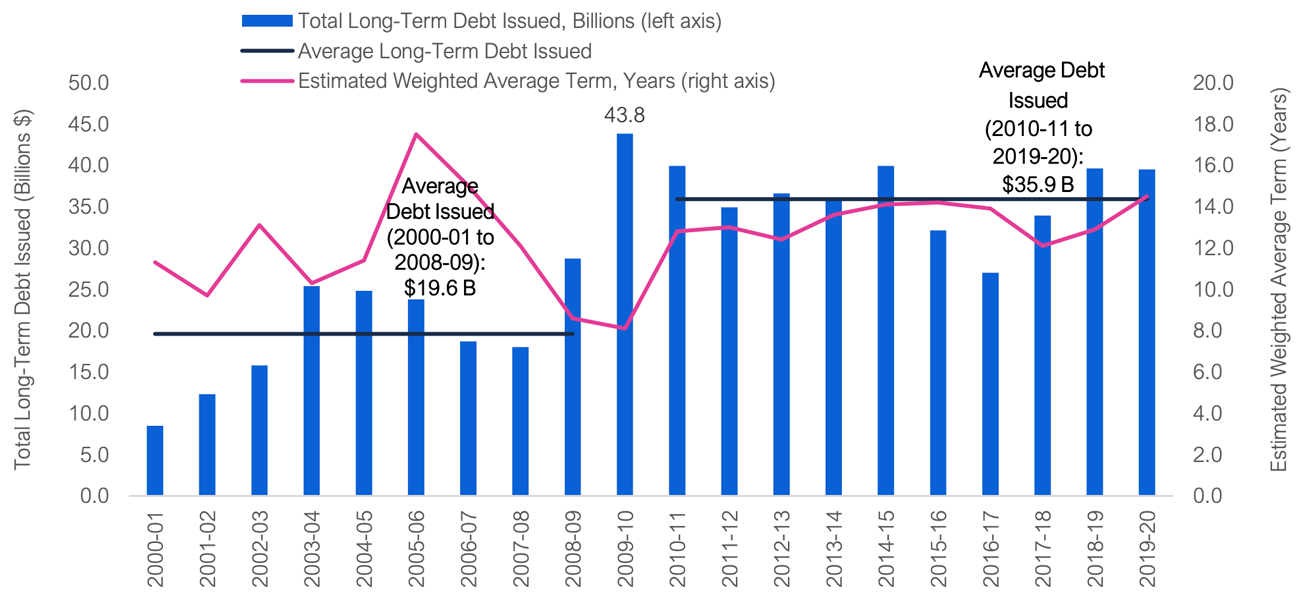

Over the last 20 years, the total amount of debt issued across various debt programs has increased dramatically. From 2000-01 to 2008-09, the average size of long-term debt issued by the Province was $19.6 billion annually. Since then, the Province has been issuing debt in larger amounts, with $35.9 billion in long-term debt being issued on average from 2010-11 to 2019-20.

Chart 5.1 Ontario’s Long-Term Debt Issues Have Significantly Increased in Size

Source: OFA, and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the total long-term debt issued in each fiscal year beginning in 2000-01 to 2020-21. The chart highlights a large increase in 2009-10, when total long-term debt issued was $43.8 billion. The projection for 2020-21 is $40.1 billion. The chart also highlights that average debt issued between 2000-01 to 2008-09 is $19.6 billion and between 2010-11 to 2019-20 it is $35.9 billion. The chart additionally includes a line representing the estimated weighted average term for debt being issued in years.

The average term for debt being issued in 2020-21 is currently expected to be 11.0 years,[10] somewhat shorter than the average term of debt issued over the past decade at 13.4 years. Generally, issuing debt with a longer term structure helps reduce fiscal risk by mitigating volatility in debt interest payments due to future changes in interest rates.

Domestic and International Borrowing

Typically, Ontario tends to undertake the majority of its total borrowing domestically, within Canada, relative to international borrowing. The Province tends to borrow in domestic markets because a group of banks referred to as a syndicate[11] purchases the bonds immediately, compared to issuing debt in foreign markets which comes with exchange rate risk.[12] Ontario remains active in foreign debt markets because it offers flexibility, expanded access and diversity in the source of funding. Although the Province bears somewhat higher costs for debt issued in foreign markets, resulting from hedging costs, most credit rating agencies view foreign market access as a credit strength.[13]

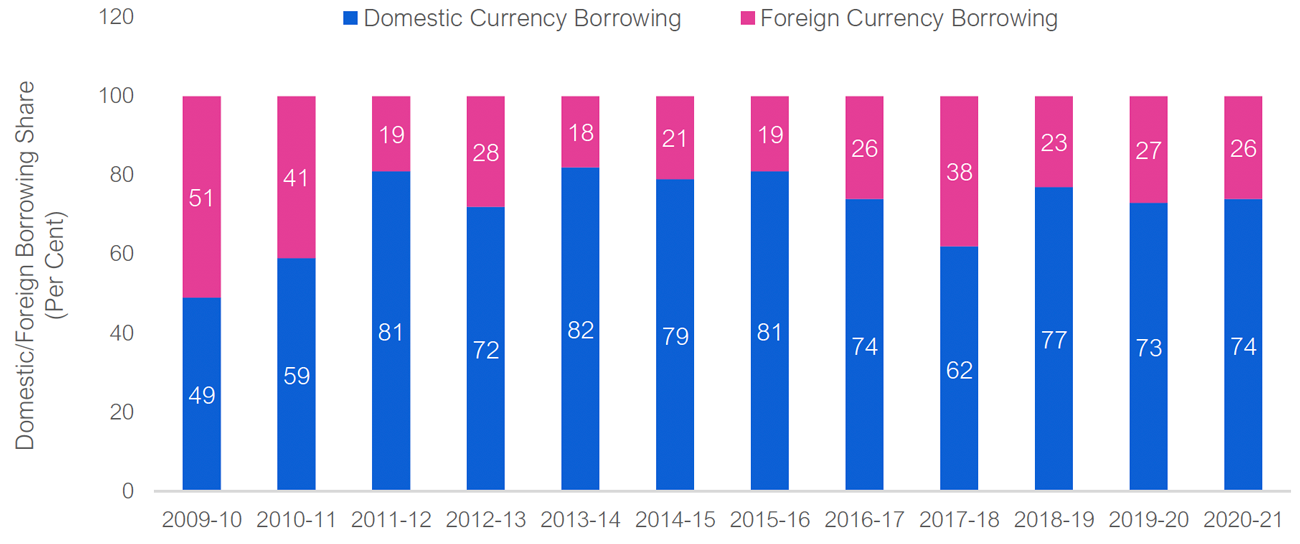

Chart 5.2 Most of Ontario’s Debt is Denominated in Canadian Dollars

Source: OFA, and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the proportions of domestic and foreign currency denominated borrowing as percentages of total borrowing in each fiscal year beginning in 2009-10 to 2020-21. In 2020-21, 74 per cent is expected to be denominated in domestic currency and 26 per cent in foreign currency.

In 2019-20, Ontario issued $39.5 billion in long-term debt, of which $28.9 billion (73 per cent) was in Canadian dollars, and $10.6 billion in foreign currencies (27 per cent), proportions consistent with recent trends.

Canadian dollar syndicated bonds accounted for 67 per cent, with Green bonds[14] and Canadian dollar auction bonds making up the remaining 6 per cent of total debt issued in Canadian dollars. U.S dollar bonds accounted for the majority of foreign currency denominated debt, representing 26 per cent of total debt issued, and Australian dollar bonds accounted for the remaining one per cent.[15] The domestic-foreign mix of this new debt is consistent with recent trends, with 74 per cent expected to be denominated in Canadian currency and 26 per cent in foreign currency.

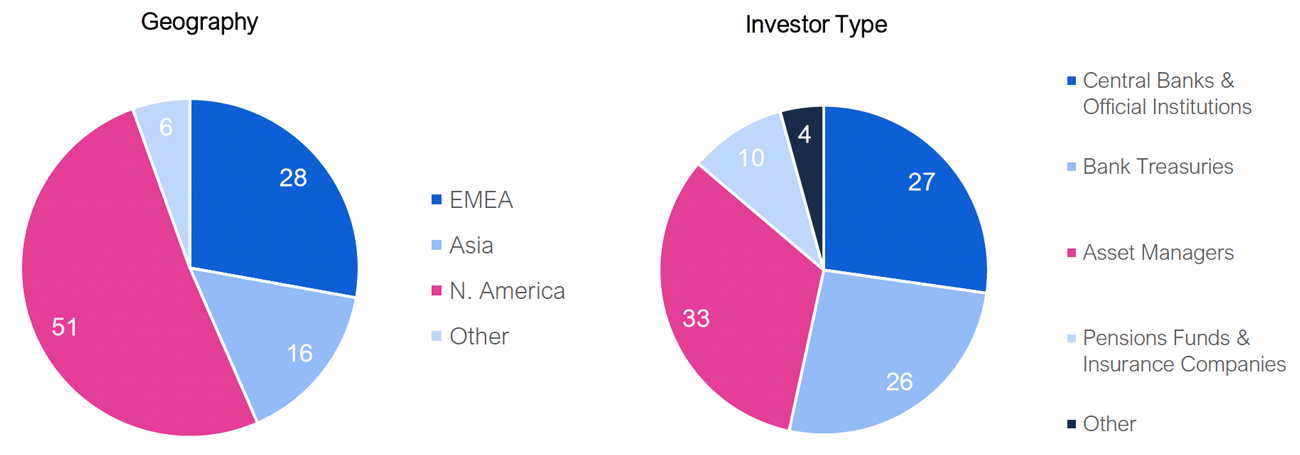

A breakdown of international bond issues since 2002-03 shows that most of the international demand for Ontario bonds is from within North America (51 per cent), followed by Europe, the Middle East and Africa (28 per cent); Asia (16 per cent) and other countries (6 per cent). Among international investors that purchase Ontario debt, the majority is held by asset fund managers (33 per cent), central banks and official institutions (27 per cent), and bank treasury departments (26 per cent).

Chart 5.3 International Investor Profile

Note: Investor data reflects debt issued in the primary market since 2002-03 to 2019-20

Source: OFA, and FAO.

Accessible version

The first pie chart shows the geographical make up of Ontario’s international bond issues since 2002-03 to 2019-20, where 51 per cent is from within North America, 28 per cent from Europe, the Middle East and Africa, 16 per cent from Asia, and 6 per cent from other countries. The second pie chart shows the proportions of international investor types, of which 33 per cent are Asset Managers, 27 per cent are Central Banks & Official Institutions, 26 per cent are Bank Treasuries, 10 per cent are Pension Funds & Insurance Companies, and 4 per cent are other investors.

6 | Appendix

Appendix A : The Ontario Financing Authority

Background

The government of Ontario established the Ontario Financing Authority (OFA) in November 1993, following the early 1990s recession. At the time, the expectation of large deficits, an elevated debt burden and higher future borrowing were key factors behind creating an entity focused on the management of Ontario’s borrowing and debt.

The Capital Investment Plan Act (CIPA), 1993, which created the OFA, also established the organization’s mandate with respect to the Province’s debt management, borrowing and investment activities. Specifically, the activities of the OFA fall into three categories: debt management, operations, and advisory responsibilities.

One of the primary functions of the OFA is debt management for the Province and the Ontario Electricity Financial Corporation (OEFC). This includes the development of a debt strategy which includes the setting of parameters for the average term of debt instruments, the domestic and foreign mix of debt issuance and policies to minimize financial risks. The OFA conducts short- and long-term borrowing on behalf of the Province by issuing various debt instruments, such as bonds, treasury bills and U.S. commercial paper, in both domestic and foreign debt markets.

The CIPA also allows the OFA to assist Crown agencies and other public bodies in their borrowing and to conduct borrowing operations on their behalf. In 2018-19 the OFA provided investment services to a number of public bodies, including Infrastructure Ontario, the Pension Benefits Guarantee Fund and the Ontario Trillium Foundation.[16] The OFA also manages all operational activities for the OEFC, which include management of electricity contracts and overall financial administration. Other responsibilities of the OFA include the provision of risk management activities and advisory responsibilities, such as planning the Province’s liquid reserves, and providing financial advice.

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Management Responsibilities | |

| Short-term and long-term debt management | Develops and administers an annual debt management strategy for the Province and for the Ontario Electricity Financial Corporation. |

| Borrowing | Manages the Province’s borrowing program, issuing provincial debt in domestic and foreign markets using syndicates and debt auctions. Acts as an intermediary or direct borrower on behalf of Crown agencies or public bodies. |

| Centralized financial services | Banking, cash management, investing, and lending to other public bodies on behalf of the Province and other Crown agencies. |

| Financial risk management | Management of credit, capital market, and operational risk. This includes administration of the Province’s liquid reserve portfolio to maximize returns. |

| Operational Responsibilities | |

| Ontario Electricity Financial Corporation (OEFC) | Manages day to day operations and financial administration. |

| Advisory Responsibilities | |

| Financial policies and projects | Provides advice on financial or capital market issues to ministries and other public bodies. |

The OFA’s Roles and Responsibilities

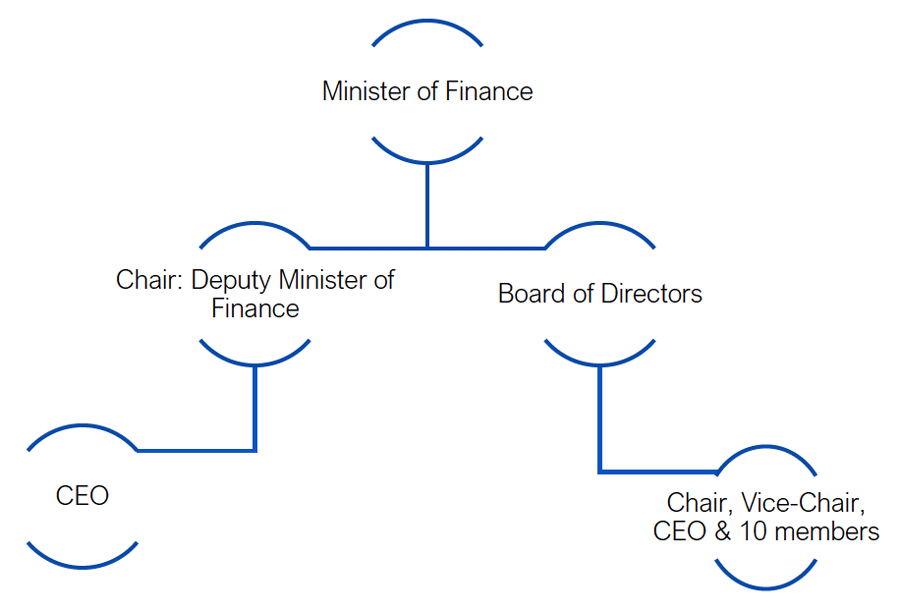

Chart A.1 Accountability Structure

Source: Auditor General of Ontario, and FAO.

Accessible version

This flow chart shows the accountability structure of the Ontario Financing Authority (OFA). At the top is the Minister of Finance, and reporting to them is the Board of Directors consisting of the Chair, who is the Deputy Minister of Finance, the CEO who reports to the Chair, and up to 10 other members.

The OFA’s organizational and reporting structure was established by CIPA. The Minister of Finance is accountable for ensuring that the OFA carries out its responsibilities in accordance with its mandate, which includes the tabling of the OFA’s annual report in the Ontario Legislature. The Deputy Minister of Finance is the Chair of the OFA and reports to the Minister of Finance on the overall performance of the organization. The OFA is overseen by a Board of Directors, consisting of a Chair, Vice Chair, the CEO and up to 10 other members.

The OFA’s Board Members are appointed by the Lieutenant Governor in Council to provide expertise and governance with regards to the Province’s debt and financial matters with support from three committees.[17] The board is required to approve the OFA’s debt management plan each year, and its operational policies. The CEO reports into the Board of Directors and supervises the day-to-day operations of the OFA.

Appendix B : Borrowing Authority in Other Provinces

Ontario has the largest borrowing authority among all Canadian provinces, reflecting the relative size of the Ontario budget as well as its relatively high level of indebtedness. For 2020-21, Ontario’s borrowing authority of $54.3 billion is almost double the size of Quebec’s borrowing authority at $31.2 billion, the second largest Canadian province. Most other provinces, with the exception of Alberta, have borrowing authorities below $10 billion. In many provinces, including British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, and Quebec, borrowing authority is set equal to borrowing requirements.

| Province | Borrowing Requirement* | Borrowing Authority** |

|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 17.1 | 25 |

| British Columbia | 8.6 | 8.6 |

| Manitoba | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| New Brunswick | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 3.2 | 2.0*** |

| Nova Scotia | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| Ontario | 66.7 | 54.3 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Quebec | 31.2 | 31.2 |

| Saskatchewan | 4.5 | 6.0 |

| Total | 127.6 | 141.1 |

Governance of borrowing authority is similar across Canadian provinces, and at the federal level, although there are differences in structure.

The federal government’s borrowing authority is established by the Borrowing Authority Act (BAA) and Part IV of the Government of Canada’s Financial Administration Act (FAA). These two Acts grant the federal Minister of Finance the authority to borrow money up to an amount approved by Parliament and is subject to extraordinary circumstances. The Borrowing Authority Act came into effect on November 23, 2017 and defines the maximum amount of federal borrowing to be $1,168 billion, based on outstanding government and Crown corporation market debt projected to the end of the 2019-20 fiscal year.[18] The BAA requires the Minister of Finance to table a report on the government’s borrowing and any recommended changes to the maximum amount every three years. The next tabling of the federal borrowing report is scheduled to occur no later than November 23, 2020.

For 2020-21, the federal government has borrowing authority of $713 billion, authorized under section 47 of the Financial Administration Act. A significant portion of this borrowing authority is allocated to satisfy the funding requirements ($469 billion) for the government’s programs in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, while a relatively smaller portion is planned to refinance debt maturities ($245 billion).[19]

For Canadian provinces, a Financial Administration Act or other comparable legislation, grants the authority to borrow to the Minister of Finance, who may appoint specific divisions within the Ministry of Finance to manage the borrowing program. Borrowing in each province is permitted up to a maximum amount either specified by a Lieutenant Governor’s Order in Council or other legislation. Generally, provincial borrowing programs and debt financing is managed by the Treasury division within the Ministry of Finance for each province. In certain provinces – Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island and Quebec – provincial borrowing authority is administered by a specific debt management division.[20] In Ontario, prior to establishment of the OFA, the Province’s borrowing, investing and debt management function was managed by the Office of the Treasury.

| Jurisdiction | Legislation | Authority | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | Borrowing Authority Act | Department of Finance | Under the Borrowing Authority Act, the Minister of Finance may borrow money up to a maximum of $1,168 billion as approved by Parliament. This aggregate amount is based on 1) market debt of the Government of Canada for the past three fiscal years 2017-18 to 2019-20, 2) borrowings of Crown corporations for the past three fiscal years 2017-18 to 2019-20, and 3) a five per cent contingency amount equal to $56 billion. |

| Alberta | Financial Administration Act (FAA) | Ministry of Treasury Board and Finance | The FAA gives the Minister of Finance the power to raise funds under an Order in Council. The Treasury Risk Management division manages the borrowing programs for the province and provincial corporations that have given authority to the Ministry to perform transactions on their behalf. |

| Alberta Capital Finance Authority Act | Alberta Capital Finance Authority (ACFA) | The ACFA is a provincial authority that acts as an agent of the Alberta Crown. It provides local entities with financing for capital projects. The ACFA has the authority to finance and refinance existing or ongoing capital projects, public works, buildings, or other structures. | |

| British Columbia | Financial Administration Act | Treasury | The Minister of Finance is the fiscal agent for the purpose of borrowing by the government, however additional person(s) may be appointed to act in this role under the FAA. The Provincial Treasury is the central government agency that manages the province’s borrowing and financing needs. Their services are extended to government ministries, Crown corporations and some public sector agencies. |

| Municipal Finance Authority Act | Municipal Finance Authority of BC (MFA) | The MFA is an independent organization which coordinates the borrowing power and requirements of BC’s municipalities by providing a collective long-term debt issuance facility. Its mandate has expanded to include investment opportunities, and several short-term borrowing options. | |

| Manitoba | Financial Administration Act | Ministry of Finance – Treasury Division | The Treasury Division, as authorized by the Minister of Finance, manages the borrowing programs and debt management activities of the government, Crown corporations, and government agencies. It also arranges the financing of municipalities, universities, schools, and hospitals. The provincial government’s borrowing authority is established under The Loan Act, which defines the maximum amount of borrowing for purposes not including the amounts to refinance debt. |

| New Brunswick | Financial Administration Act | Ministry of Finance – Treasury Division | Manages and administers the cash resources, borrowing programs, and all investment and debt management activities of the government; arranges the financing for the borrowing requirements of Crown agencies (including NBMFC), municipalities and hospitals. |

| New Brunswick Municipal Finance Corporation Act | New Brunswick Municipal Finance Corporation (NBMFC) | The objective of the NBMFC is to provide financing for municipalities and municipal enterprises through a central borrowing authority. | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Financial Administration Act | Ministry of Finance – Pensions and Debt Management | Responsible for the Capital Markets and Financial Assistance Programs, including the administration of the Province’s loan guarantee and borrowing programs. The Loan Act authorizes the raising of funds through loans by the Province. |

| Nova Scotia | Finance Act | Department of Finance and Treasury Board | Under the authority of the Minister of Finance, the Department of Finance and Treasury Board manages the Province’s debt portfolio and borrowing programs. |

| Municipal Finance Corporation Act | Nova Scotia Municipal Finance Corporation (NSMFC) | The NSMFC is a Crown Corporation which acts as a central borrowing agency for municipalities and municipal enterprises. The NSMFC has the legislative authority and ability to issue serial debentures to fund long-term capital requirements through capital markets with a provincial guarantee. | |

| Prince Edward Island | Financial Administration Act | Department of Finance – Debt and Investment Management | With the Minister of Finance’s authority, this division is responsible for the development of debt management strategies, arranging project financing, and the asset/liability management of Crown corporations. |

| Quebec | Act Respecting the Ministere des Finances; Act Respecting Financement-Quebec | The Financing Fund and Financement-Quebec | The Financing Fund was established by the Act Respecting the Ministere des Finances and has a mandate to provide pooled financing to public government bodies including school boards, health and social services establishments, and government enterprises. Financement-Quebec is a corporate body with a similar mandate; however, it provides services to other public bodies including municipalities. |

| Saskatchewan | Financial Administration Act | Ministry of Finance | The Ministry is responsible for providing cash management, investment, and capital borrowing services for the General Revenue Fund, Crown corporations (including the MFC), and other government agencies. The Minister of Finance has the authority to borrow up to a maximum amount set by an Order in Council under the province’s Financial Administration Act. |

| Municipal Financing Corporation Act | Municipal Financing Corporation of Saskatchewan (MFC) | The MFC is responsible for assisting municipalities in financing their capital requirements. The MFC is an agent of the Crown and administered by the Ministry of Finance. Under the Act, borrowing authority is subject to the approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council up to a maximum amount. |

Footnotes

[1] An Order in Council refers to a legal order by the Lieutenant Governor, made on behalf of the Premier or a Minister. Borrowing authority can be comprised of multiple OICs.

[2] The total funding requirement reflects the government’s projected budget deficit, planned capital expenditures, other loans, and accounting adjustments. See Table 3.1 Borrowing Program, in the March 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update, page 45.

[3] The FAO projected a budget deficit for 2020-21 of $41 billion, and a funding requirement of $72.8 billion. See the FAO’s Spring 2020 Economic and Budget Outlook for details. The FAO will release an update of its Economic and Budget Outlook report in early fall which will include an updated assessment of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Ontario’s finances.

[4] See Appendix A for a discussion on the Ontario Financing Authority and its roles and responsibilities in managing the Province’s borrowing and financial activities.

[5] Or entered into an agreement to use the borrowing authority.

[6] See Appendix B for a provincial comparison of borrowing authority.

[7] In 2018-19, additional borrowing authority of $1.9 was required due to adjustments in the deficit as a result of reporting and accounting changes. For more details see the Report of the Independent Financial Commission of Inquiry.

[8] Domestic programs include Domestic Medium-Term Notes, Ontario Savings Bonds (legacy debt only), and Treasury Bills. Internationally, the Province issues debt through the Australian Debt Issuance programme, the Euro Medium Term Note programme, Global Bonds, and the U.S Commercial Paper program. See the OFA’s Debt Issuance Programs for more details.

[9] See page 581 of the Auditor General of Ontario’s Annual Report, 2019.

[10] The average term of debt issuance reflects data as of July 23, 2020.

[11] The Province typically sells debt instruments directly to a syndicate of Canadian banks that include National Bank of Canada, Toronto Dominion Bank, Bank of Montreal, Royal Bank, Scotia Bank and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, which then resell the debt to institutional investors.

[12] Exchange rate risk refers to exposure from changes in the Canadian dollar foreign exchange rate which can result in volatility in the Canadian dollar value of interest payments. This risk can be mitigated through hedging.

[13] See the latest DBRS Morningstar’s Rating Report, Moody’s Investor Service Credit Opinion, S&P Global Ratings, and Fitch’s Rating Action Commentary for details.

[14] Green Bonds are debt issues for infrastructure projects with environmentally positive outcomes such as clean transportation, energy efficiency and conservation, clean energy and technology, forestry, agriculture and land management and climate adaptation and resilience. Ontario currently has seven Green Bond issues totalling $5.25 billion. For more details see the OFA’s Province of Ontario Green Bonds.

[15] See the OFA’s "Province of Ontario Presentation."

[16] See the Ontario Financing Authority 2019 Annual Report.

[17] The committees supporting the board are the Human Resources and Governance Committee, the Audit and Risk Management Committee and the Ontario Nuclear Funds Agreement Investment Committee. For more details see the Auditor General of Ontario’s Annual Report, 2019.

[18] Prior to 2017, Canada’s borrowing authority was governed only by the Financial Administration Act. See the Parliamentary Budget Officer’s The Borrowing Authority Act and Measures of Federal Debt.

[19] See the Federal Government of Canada’s Economic and Fiscal Snapshot 2020, page 160.

[20] See Table B.2 for more details.